When paleontologists only have so many clues to infer a fossil’s original form, it’s all too easy to make honest mistakes. Sometimes, supposedly reasonable assumptions set researchers on the wrong path—as demonstrated by a “rediscovered” creature sporting an unlikely mix of reptilian features.

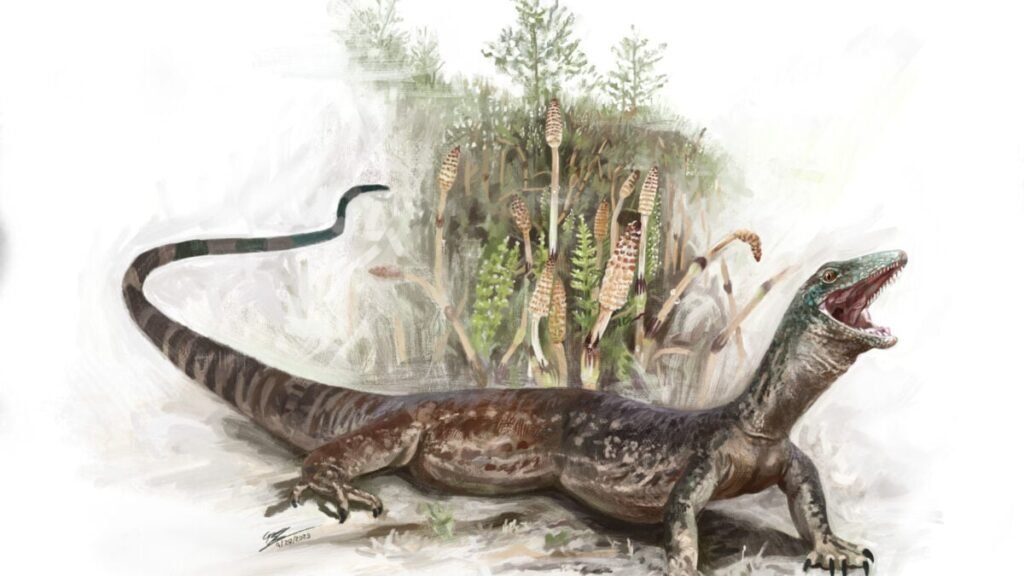

A Nature paper published today introduced to the world Breugnathair elgolensis, a reptilian creature from the Jurassic era with the short body and limbs of a gecko. But like its name, Gaelic for “false snake of Elgol,” its jaws and hooked teeth resemble that of modern-day pythons. The combination was so seemingly impossible that when paleontologists first unearthed the fossil in 2015, they naturally assumed that the set of bones belonged to separate animals.

The reclassification places Breugnathair in a group of extinct squamates—an order of reptiles including lizards and snakes—called Parviraptoridae. This group itself was known to be enigmatic to paleontologists, as most “individuals” in the group were comprised of fragmented fossils with unidentified pieces, according to the researchers.

Revisiting the fossil

For the study, the researchers performed a combination of 3D imaging techniques and X-ray scans to create a detailed reconstruction of the fossil. They also compiled a comparative family tree using three independent datasets on the genetic information of early reptiles, squamates, and a subset of squamates including snakes, monitor lizards, and iguanas.

From their analysis, they put together a nearly complete skeleton of a strange hybrid creature with traces of both lizards and snakes. The resulting creature, about 16 inches long from head to tail, looked uncanny but technically made sense. The “seemingly chimeric individual is indeed a genuine parviraptorid,” Hussam Zaher, a paleontologist at the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil, wrote in an accompanying News and Views.

Slinky origins

On one hand, the rediscovery raises serious questions about how well we understand the origin of snakes. The consensus had been that snakes separated from lizard-like creatures, although the exact evolutionary pathway “remains incompletely understood,” Zaher explained.

To be clear, the paper’s authors are not suggesting that snakes evolved from Breugnathair. The reptile’s size was relatively large compared to other similar species at the time, so it likely preyed on smaller lizards or baby dinosaurs. Whether Breugnathair is an evolutionary oddball or a creature that reflects some larger trend in the genetic history of snakes, the researchers can’t be sure.

“Breugnathair has snake-like features of the teeth and jaws, but in other ways, it is surprisingly primitive,” Roger Benson, study lead author and a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History, explained in a statement. “This might be telling us that snake ancestors were very different [from] what we expected, or it could instead be evidence that snake-like predatory habits evolved separately in a primitive, extinct group.”

“The mosaic of primitive and specialized features we find in parviraptorids, as demonstrated by this new specimen, is an important reminder that evolutionary paths can be unpredictable,” explained Susan Evans, study co-author and a paleontologist at University College London in the United Kingdom, in the same release.

“This fossil gets us quite far, but it doesn’t get us all of the way,” Benson added. “However, it makes us even more excited about the possibility of figuring out where snakes come from.”